Despicable Me

by Scott

I’m forty-two years old and should know better.

Correction: I do know better.

I’ve been married eleven years and have a beautiful eight-year-old daughter, and have been with my wife twenty-five years give or take. My wife’s parents split a few months before we started dating, and eventually divorced, and this event still has an effect on her family today.

The story of my own parents’ split is a little more complex. When I was twenty my dad left home to live with another woman. He came back not long after, then left again, only to return once more. This began in 1995 and continues to this day; he spends nine months of the year abroad with this other woman, and the remainder of the year at home with my mum. My mum knows he’s with this other woman but he denies it. He doesn’t deny her existence, or even that she lives on the same island as he, but he denies that they’re living together, insisting still, after countless years, that his only purpose for being there is business.

This split (if you can call it that, because they’re still together, or at least they’re together for the off-season months through each winter), but this split has had a devastating impact on my life; it’s affected my relationship with both my mum and dad. He’s treated her abominably and yet I find myself thinking she’s her own worst enemy, facilitating his ongoing charade by refusing to leave him. The truth is she’s afraid of growing old alone, and yet she’s been growing old alone for three-quarters of each of the last twenty years.

Now I’m far from perfect. I’m lazy at times, stuck in a dead-end job with no prospects, moody as often as I’m lazy, and I detached myself from my in-laws for my own sanity many years ago; but I do know the difference between right and wrong, I respect the law, and I know my own mind regarding my morals, or at least I thought I did until very recently. I’ve never been unfaithful to my wife. I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t live with the guilt let alone witness the consequences shape the future life of our precious daughter.

And yet here I am, writing this because it’s the only means I have to comprehend what’s happening and what might yet happen. I haven’t felt like this about somebody else for as long as I can remember and, in truth, I’m just a little bit frightened. I vaguely recall the symptoms from many years ago: the loss of appetite, the lack of sleep at night and enduring lethargy during the days, an inability to concentrate, a giddy mixture of fear and euphoria, of nervousness and composing sentences which might one day be used, and the combination of all of these things equalling a perpetual queasiness which results in my feeling nothing really matters.

I met her professionally. She’s the student and I’m her teacher. That’s how our relationship is and how it has always been. I’ve always thought the learner driver’s relationship with his or her instructor a strange one because it’s more than a student/teacher relationship, it’s a client/business relationship, and at the same time an employer/employee relationship, and because of these things, I think, there’s often a moral minefield before we’re anywhere near discussing the relationship status of the two parties.

You can learn to drive at 17 in the U.K. and many youngsters take their lessons at such a young age. The majority of my students, I’d guess, though I’ve never calculated, are around 18 years old. She, lets avoid a name here, is 29. She’s been married for as long as I have and has three children aged 13, nine, and two. I’ve known her just over seven months and she’s only ever referred to her husband as “him”, “he”, or “my other half”, though I’ve no reason to think they have in any way a poor relationship. I don’t know, though I suspect not. We’ve talked many times about our families and she’s said nothing to suggest this.

So despite our respective marriages and children, and that I know what is morally right and wrong, and that I’ve been affected directly by infidelity and have seen how it reshapes people’s lives, how it breaks them into tiny pieces which sometimes can be glued together again, though not always so the cracks don’t show; despite all these things why do I feel this way about her? How have I let myself get to where I am now?

I think my writing this is a way of searching for an answer.

There’s nothing specific about her that has drawn me. She has nothing I’ve not seen and admired in women before, and she certainly has nothing to offer that my wife doesn’t. In some ways she has considerably less. She’s from the wrong side of town. If you think that a cliché you should walk through the Lunt after dark. Her limited vocabulary perhaps reflects a lack of education typical of our town, and yet the soft assuredness of her voice is instantly appealing, as is the way she’s unable often to articulate what she wants to say, which results in her sentences hanging, unfinished, until she punctuates them with a delicate, almost wistful, yeah.

Sometimes, when I know what she’s trying to say, which when we’re discussing her driving is often, I finish those sentences, then find myself wishing I’d allowed her more time to finish herself. When I do allow that time the ensuing silence becomes uncomfortable, and so I step in once more.

Maybe it’s the veneer of quiet reserve she displays that occasionally slips when our conversation moves away from her driving and onto other subjects. Maybe it’s the way she giggles at her occasional clumsiness on the clutch or a missed gear change, or maybe it’s the childlike noise she makes, teeth clenched, warm cheeks puffed out, when she attempts to stifle those giggles.

Those cheeks. They’re always red but never rouged. They’re warm and in a curious way inviting. Sometimes they appear blushed as if there’s a nervous flurry of self-consciousness. They’re blemished, too, in a minor way that recalls teenage acne, like its clinging on, refusing to go away.

I’m fascinated by her forearms. They’re thickset and don’t narrow at the wrist. One of them has drawn on it a spiralling vine, and there, in tiny lettering at the end of two of the vine’s tendrils, are the names of two of her children. I’ve never seen the third name but assume it’s either hidden by a sleeve or is maybe on the other side of her arm. There’s ink on her shoulder, also, which is distracting when she arrives at a junction, and we’re both looking right for traffic but my eyes are drawn to this tattoo, a shaded star, large in size, only a portion of which is visible.

There are other things, too, physically, which I find attractive, and yet they’re not remarkable things. She is in many ways unremarkable, and yet, to me, has become more and more remarkable. I couldn’t say, if asked, when this started to happen, when my fondness for her in a friendly, professional way, in a way that meant nothing more than looking forward to and enjoying her lessons, began to develop into how I feel about her now. I suspect only within the past two or three weeks, subconsciously at first, and then, a week ago or so, like a punch to the stomach, it, whatever it is, struck me.

I look for her as I drive through the Lunt, excited and fearful at once, hoping both to see her and to not, and not knowing how to react if she sees me. I drive through there often while working, on the way to collect pupils, and then with those pupils on their driving lessons. I drive through there with my wife and daughter on the way to my daughter’s swimming lesson, or on the way to lunch maybe, and feel guilty for thinking about her then.

She’ll pass her driving test eventually and I don’t know what will happen after that. I know what should happen and I know what I think will happen, and they’re the same thing. But sitting here writing this, actually feeling nervous tapping out this confession, feeling tiny butterflies in my stomach, I feel as though I can’t make any promises.

***

About the author:

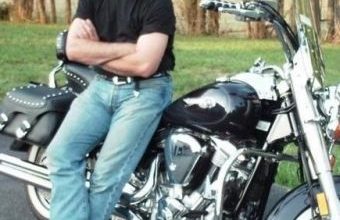

Scott is 42 years old and lives in Bilston, in the heart of England’s Black Country, with his wife and daughter and two perma-hungry guinea pigs.

He’s had both fiction and non-fiction published online and in print. His stories have appeared in Southern Pacific Review and Clamor, amongst others, and he won Southern Pacific Review’s annual fiction prize in 2016 with his story Mrs Delaney’s Crumbling Facade. His non-fiction, mostly football oriented, has appeared in These Football Times, The Daisy Cutter, and King of the Kippax.

Scott’s first novel, In Elisabeth’s Shadow, a story detailing the real life fight to prevent the closure of Bilston Steelworks, is currently doing the rounds of literary agents. His second, Rubery Murder’s On Moxley Cut, is the author’s attempt to understand his own dislike/fascination with reality TV and the modern concept of celebrity, and is very much still a work in progress.

When he’s not writing, Scott dreams of being able to style his hair like a young Steve Marriott. He thinks dreaming’s important.