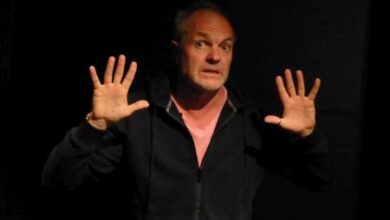

Interview With Author, Matthew Tysz

Matthew Tysz is a homebody at heart, though possesses this strange fondness for city life and, like the great H.P. Lovecraft, has an especially painful attraction to Manhattan (a place which he has lovingly destroyed in several stories).

Matthew loves people, though often finds he keeps them at arm’s length. He loves watching people, ruminating on their behavior and building little stories out of predictions as to what each man or woman he sees is going to do next. Most especially, he likes to imagine them in different settings, extraordinary settings, and ponder the discoveries of such extreme displacement.

He states: I always believed that chaos is the muse of creation, and a good story is often driven by the choices made in the wake of madness.

Firstly, must ask, is it Tysz like ‘size’ or Tysz like ‘fizz’, or something else entirely?

Matthew Tysz: Tysz as in ‘size.’ Before Ellis Island, it was Tyszkiewicz, but I’ll spare my fuse box trying to figure that one out.

Your Amazon page speaks to a rather prolific writer! How many books have you completed to date?

To date, I have nine novels finished and self-published on Amazon, almost done with number ten. I have a pair of short stories also published, but as a general rule, I prefer my short stories on the much longer side.

Where can we find those? And why do you prefer stories on the longer side?

My short stories can be found on Amazon as well, although they are on full display for free on my website, www.matthewtysz.com. I prefer longer stories because I love to fall in love with a story; I love to become involved in the expansive mythos of a world and the characters who inhabit it. I seek to make others feel the way such stories have made me feel; I want such expansive worlds to stand in my name, visited and enjoyed by those who have an appreciation for it.

Your bio mentions a ‘painful attraction to Manhattan’. As a resident of flyover country, I always assumed New Yorkers felt much the same way about Manhattan as Floridians about Disney World: What is it about the core of the Big Apple that attracts you as a writer?

If you think about it, most of New York is what (New Yorker) Alec Baldwin might call ‘flyover.’ but Long Island, where I grew up, is a different place from both the city and the continental state. It’s an island overloaded with suburbs, commercialization, and poorly-laid out roads; it’s a place with too much going on yet still manages to be boring. The further east on the island you get, the more you escape the overcrowding, but not the boredom. It’s home, but it’s lonely. Manhattan is a place that has an excuse to be as wild as it is.<

But to answer the question more precisely, I’m a people watcher. The more people, the more variety among those people, the more activity going on in their lives to witness, the more I find there is to learn about them, both about myself and about my world. The stories I tell are founded on its characters; they’re the most important part of the story. There is no university for a human study like Manhattan.

You also write in your bio “I’ve always believed that chaos is the muse of creation…” What do you mean by that in specific terms? I think for most writers chaos is kind of a double-edged sword. Do you differentiate between different forms of chaos? What about your process comes from chaos versus discipline?

I’m not sure I believe that chaos has to stand in opposition to discipline. In fact, if you have a crowd of disciplined people, whose disciplines take each of them in different directions, you can easily have chaos. But where did the chaos begin exactly? How does did spread? Can it be stopped at an affordable cost? These questions bring us back to the study of people, the premier harbingers of chaos.

I agree. I think what I meant by chaos v discipline mostly relates to the process. The real world is definitely chaotic (especially now) but writing — especially a book, especially a series — requires some degree of a methodical approach. In layman’s terms, how do you refine chaotic influences into a book? How do you decide what belongs in the book you are writing versus what doesn’t? For example, do you select characters based around a central plot or does the plot develop organically from one or more interesting people you have seen?

The subconscious is chaotically bombarded with constant influences big and small, and since we can never reach too deeply into our own subconsciousness, It’s difficult to say where the chaos ends and the methodology begins. First and foremost, it’s important to relax: the chaos of the world, the chaos of the mind, will never stop, but why does it have to? When you relax, when you let your mind work, you will find order in all that goes on around you. You’ll realize what you want to see, and you’ll see how the threads you’re spinning can give structure to your imaginings.

Figuring out what does and does not belong in a story gets easier with experience. Once your methodology for weaving a story progresses (which comes simply through repetition), you’ll find there isn’t a lot there that did not belong to begin with. But it still happens from time to time, and when it does, I admit it’s often a weakness of mine. I like to pack so many things into a story, there are times I go a little overboard. The solution comes down to the language of your story: what are you trying to say? Are you giving a job to two different characters that one character can do?

You identify H.P Lovecraft as a central influence. What is it about Lovecraft you find the most impressive as a writer? Are you more drawn toward the themes? The general mythos? The writing style? What unique lessons do you feel Lovecraft offers?

The writing style? Heavens no. As much as I love the man, I have to say I find his prose, while eloquent, is flowery to a fault. The themes? Now there’s something I can work with.

As a writer of post-apocalyptic fantasy, one of my favorite plot devices is general hopelessness. As a writer of apocalyptic fantasy (big difference), authors like H.P. Lovecraft and Garth Ennis are fabulous professors of hopelessness. But finally, my favorite part of Lovecraft is his general mythos. Second only to characterization, world-building is the most important thing to me; it’s what makes a story truly immortal, keeps readers coming back, and encourages the expansion of an interesting universe. The Legacy Lovecraft built is one I envy even more than that of Tolkien himself.

World building is something that often comes up on the forum, so I would like to explore that briefly. For those starting out, what do you believe to be the best way to approach constructing a fantasy world? Do you take a structuralist view by essentially borrowing and re-configuring real-world features, such as currency, language, etc, or do you try to completely re-imagine everything? How similar are your created worlds to the real world, in general?

The thing about having existed for some four thousand years is that human civilization has, from a practical standpoint, gotten a lot of things right. Even if you can change the nature of the world, you can’t change the nature of humanity, and that’s mainly what people want to read about: the themes of good and evil, greed, grief, perseverance and survival, love, anger, the horrors of indifference. Without these themes, there’s very little reason for a general audience to engage in a story. So I do a lot of reflecting, taking elements from the real world and “putting them to the test” in a different world, perhaps highlighting and exploiting certain human elements that we, in the real world, don’t often see in our regimented and relatively predictable lives.

It looks like many (most?) of your published works form part of quite extended series. Why is that? What advantages do you feel a series offers?

Yes. Five (out of a future nine) of my currently-published books belong to the “We are Voulhire” series, three (out of a future five) belong to “The Turn” series, and then there is my one standalone (so far), “The Last City of America.” As I mentioned before, I’m a sucker for characters and world-building; this leads me to write stories that are longer, layered, and often demanding of an episodic style of storytelling. You fall more deeply in love with the world that way, and of course, with the characters.

A lot of your work seems quite dark in tone, perhaps even nihilistic, yet you describe yourself as somebody who ‘loves people’. What drives you toward your subject matter?

As I mentioned before, I have a penchant for implementing hopelessness into my stories. There are two reasons for this. One: I often like to introduce a relief of hope only after an introduction of oppressive hopelessness, thus making said relief more effective. Two, and this perhaps ties in with the nihilistic aspect you noticed: I enjoy the thought of not having to rely on hope, but on the inconsistent, sometimes tangential unpredictability of human nature. People can be saints, they can be monsters, but their diversity inspires me. No artist worth his weight in dirt can bring himself to hate that which inspires him.

Which of your books are you most proud of and why?

That’s like asking a mother which of her children she loves the most. One thing I can say: the closest thing to a trophy I can identify among my arsenal of literary elements is my villainy. I have three books whose plot-lines are centered on three of my best villains. With that in mind, I would have to tentatively say “The King of May” is the best showcase of my best strong suit.

Villains, that’s another frequently discussed topic. What is most important to you when creating a strong villain? Do you prefer villains that are, well, villainous or more checkered, more antagonistic rather than evil?

I love evil. I’ve always been fascinated by it. However, I also believe that people are good at heart. Everyone is capable of both. This is another aspect of humanity I like to bring into the consideration of my reader: does redemption have limits? Are there people who are truly, purely unrepentant? I like to push that limit, creating the most twisted characters while peppering them with empathetic elements. Sometimes I’ll break a serial killer’s heart. Sometimes I make a rapist funny. While the occasional “mustache-twirler” can be loads of fun, even embellishing of a larger story, I think it’s generally a mistake to let an audience forget that villains are people too.

Do you self-publish? What advice would you give beginning authors about publishing/selling work?

I do self-publish, and as a beginner myself, I think I would be much better served to receive advice than anyone else would be by taking mine. If you’re trying to make serious sales, just remember that Amazon is not your friend, they’re your boss. They want consistent results month-to-month or you’ll free-fall in the rankings; no one will ever notice you and no one will ever love you. So don’t let that happen.

Complete this sentence: “Hell is…..”

Loneliness.

Can’t argue with that!Thank you, Matthew.

Visit Matthew Tysz website for more information: www.matthewtysz.com

Read more Flashes author interviews